- The alliance has been positioned as America buttressing its two allies against the ambitions of Iran and Turkey, but sceptics spy a quid pro quo

- US wants Arab-Israeli support in countering Beijing’s influence over supply routes seen as a ‘life and death’ matter for China’s economy, analysts say

US President Donald Trump smiles after announcing that the United Arab Emirates and Israel have agreed to establish full diplomatic ties. Photo: AP

The United States is actively seeking to leverage its pivotal role in establishing diplomatic relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to intensify its resistance to China’s Belt and Road interests in the Middle East, Horn of Africa and the eastern Mediterranean.

The framework of the trilateral agreement, announced on August 13 by the UAE’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash and lauded as historic by the Trump administration that brokered it, contained plans for a maritime security alliance, analysts and commentators told This Week in Asia.

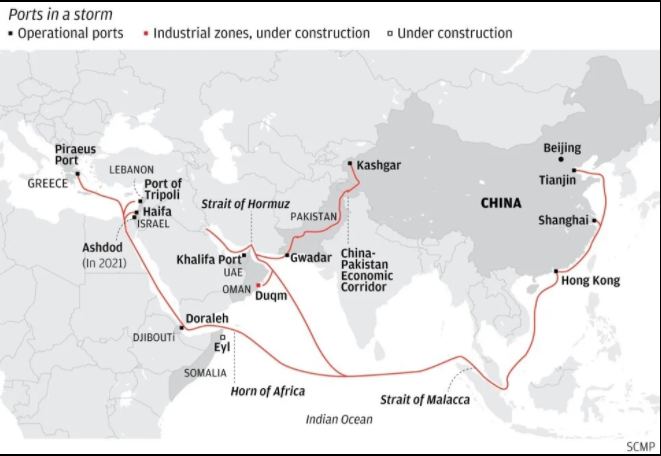

Once implemented, the trilateral alliance will establish a “strategic triangle” which, primarily, aims to counter Iranian threats to shipping passing through the region’s two maritime choke points: the Strait of Hormuz, at the entrance to the hydrocarbon-rich Gulf, and the Bab El-Mandeb Strait between Yemen and the Horn of Africa, on the way from the Indian Ocean to the Suez Canal.

Alongside the Strait of Malacca – a strip of water between Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra – they comprise the three strategic maritime passages most important to China’s geopolitical interests. Beijing has described unhindered access to the three waterways as a “matter of life and death” for its economy.

The US-led trilateral maritime alliance further aims to contest Turkey’s assertion of a vastly expanded claim to an exclusive economic zone covering most of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, following its agreement last November with the Tripoli-based United Nations-recognised government of civil war-torn Libya.

Tensions have also risen between China and Turkey over its military intervention in support of the Libyan government, and over President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s diplomatic handling of China’s controversial mass detention of Uygur Muslims, a Turkic ethnic group.

“The Israel-UAE deal is partially aimed at formalising cooperation on maritime security and on combating threats to vital supply routes,” said Samuel Ramani, a commentator on Middle East affairs and doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford.

He expects “cautious” logistical, joint drills on maritime security supervised by the US, at least initially, as well as joint Israeli and Emirati membership in a US-led maritime security coalition – like the one it formed against Iran last year – as potential outcomes.

“It’s too early to see how this plays out, but already there are concerns in Beijing about what this means for the Belt and Road Initiative,” Ramani said.

More than maritime shipping, however, he said China suspected “hidden strings” may have been inserted into the US-Israel-UAE agreement by Jared Kushner, President Trump’s senior adviser and son-in-law.

“It may be understood by all parties that the US is promising trilateral economic cooperation at the expense of China,” said Kelsey Broderick, China analyst for the Eurasia Group, a New York-based geopolitical risk consultancy.

“ Managing US-China rivalry will remain a daunting challenge, even for the shrewd and capable Emiratis

Ben Scott, Rules-Based Order Projec

“However, it seems unlikely that the US asked for a list of specific anti-China measures from Israel and the UAE as a component of the deal,” she said.

Ramani said the agreement was also greatly influenced by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who since 2018 has ratcheted up pressure on Washington’s Middle East allies to pick sides in its diplomatic and economic confrontation with China.

“The US certainly is paying more attention to the China-UAE relationship than ever before,” Ramani said.

The US State Department has been “especially vocal about the need for countries in the Gulf to choose between the US and China,” he said.

China is a major trading partner of the UAE and Israel. Emirati ports transship about 60 per cent of all westbound Chinese maritime trade, and the UAE accounts for 28 per cent of China’s non-oil trade with the Middle East, the principal source of oil for the world’s biggest importer. The UAE is home to more than 4,000 Chinese companies doing business throughout the Arab world and Africa, and to some 200,000 Chinese nationals, earning Dubai the nickname “Hong Kong east”. Most Chinese firms are based at the Jebel Ali free zone operated by Dubai’s state-owned DP World, the leading container terminal operator in the Arabian Peninsula and South Asia.

In neighbouring Abu Dhabi, the largest of the UAE’s seven emirates and its seat of political power, Cosco Shipping Ports has established its Middle East hub at Khalifa Port – 25km south of DP World’s mother hub of Jebel Ali. Leveraging its joint venture there with the leading European shipping line Geneva-based Mediterranean Shipping Co (MSC), the Chinese maritime industry leader boosted cargo volume at Khalifa Port by 82 per cent within six months.

Kamran Bokhari, director of analytical development at the Centre for Global Policy (CGP), said Abu Dhabi’s recent actions had much less to do with Israel specifically than they did with the UAE’s “efforts to try and manage a precarious regional security vacuum”.

“It has to do with the Emirates’ efforts to assume charge of Arab diplomacy in order to manage regional security interests at a time of uncertain American intentions and when Turkey is pressing ahead with its efforts to become the hegemon in the Middle East,” Bokhari said in a recent analysis published by the CGP, a think tank based in Washington.

Thus far, the UAE has enjoyed the US security umbrella, but “that umbrella is becoming increasingly unreliable as Washington has been moving away from heavy lifting vis-a-vis regional security needs”, he said.

“Abu Dhabi knows that the US strategy for the Middle East increasingly relies on regional players to take the lead, and this is driving Emirati behaviour,” Bokhari said.

Ben Scott, director of Australia’s Security and the Rules-Based Order Project at the Sydney-based Lowy Institute, said Abu Dhabi’s growing doubts about Washington’s resolve and staying power had accelerated its growing ties with China.

This has further deepened the divergence of interests in the region between the US and the UAE.

Abu Dhabi has distanced itself from Washington’s policy of sanctions-based “maximum pressure” towards Iran, which it fears could provoke a devastating war in which its oil-production facilities, ports and free zones would be targeted.

It has also parted ways with the US in Syria, which the UAE has worked to bring back into the fold of the Arab League, both to counter Turkey’s military intervention and to reduce President Bashar al-Assad’s economic dependence on Iran.

“Abu Dhabi needs to realign with the US foreign policy consensus. But there are few foreign policy issues on which Republicans and Democrats still agree. The fact that one of those points of agreement is opposition to China has only added to the UAE’s problems,” said Scott, in a report published by the Lowy Institute.

He said the UAE’s decision to “normalise” relations with Israel was driven by its need to strengthen bipartisan support in the US Congress and improve its image with the administration that will take power after presidential elections in November.

“The UAE has gone a long way to restoring its standing in Washington and probably given itself more room to move with China. But managing US-China rivalry will remain a daunting challenge, even for the shrewd and capable Emiratis,” Scott said.

As for Israel, its exports to China almost quadrupled between 2009 and 2018, hitting US$4.79 billion, according to World Bank data. Its imports more than doubled to US$10.46 billion in 2018, making China its second-largest trading partner behind the US.

Meanwhile, the state-owned China Harbour Engineering Co (CHEC) is developing Israel’s second commercial port at the town of Ashdod.

The Chinese investments have taken place as part of Israeli government reforms to expand and privatise its ports. Chinese firms are expected to be leading contenders for stakes in Haifa and Ashdod ports.

The British oil tanker Stena Impero is surrounded by speedboats of Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guard Corps in the Strait of Hormuz. Photo: Xinhua

China’s concerns have been fuelled by Pompeo’s recent ultimatum to Israel and the fallout.

During a visit to Jerusalem in May – his first overseas trip since the coronavirus pandemic – Pompeo reiterated warnings that Washington would reduce intelligence sharing with Israel if it allowed large-scale Chinese participation in infrastructure projects.

Soon after, an expanded security review of Chinese investments being conducted by Israel under US pressure kicked in: it rejected the practically confirmed bid of a Hong Kong-based conglomerate founded by tycoon Li Ka-shing to build the US$1.5 billion Sorek-2 water desalination plant

Israel has also agreed to exclude Chinese equipment from its 5G wireless internet networks, according to recent reports.

But the US, which is in the process of withdrawing combat forces from the Middle East, has demanded a more exorbitant price for buttressing Israel and the UAE against their regional competitors Iran and Turkey: it wants Abu Dhabi and Jerusalem to act in concert with it against Beijing.

“It definitely seems that Washington is trying to convince some Middle East countries to choose between aligning with either China or the US, likely with an eye on China’s expanding investments in the region,” said Broderick.

Washington is seeking to belatedly avert Beijing’s fait accompli of building a vast network of ports and industrial free zones stretching from South Asia to the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa.

China is very close to connecting its “string of pearls” network of military and commercial facilities in the Indian Ocean with the one it is building along the eastern Mediterranean seaboard

Shanghai International Port Group is due to launch operations next year at a new container terminal it is developing at Israel’s sole commercial port of Haifa, under a 25-year lease signed last year.

Despite Pompeo’s claims that China could use it to spy on the US Navy, which frequents the port, Israel has rejected Pompeo’s demands to cancel the Chinese lease for Haifa. Israel had faced the most US pressure, Broderick said, “but I doubt Israel will act against the belt and road to the same extent as the US, unless China-Iran security cooperation significantly ramps up”.

China and Russia recently led opposition to a failed US attempt to indefinitely extend the UN Security Council’s embargo on arms sales to Iran, which will now expire on October 18.

Since 2012, CHEC has also worked to rehabilitate the northern Lebanese port of Tripoli, which markets itself as a logistical hub for Syria.

Hong Kong-based Cosco Shipping Ports launched a mainline container service to Tripoli port late last year.

Cosco and its partner shipping lines would add them to service loops meeting at the Greek port of Piraeus, which it has majority owned since 2016.

Working primarily with MSC, which has since become its partner at Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi, Cosco has transformed Piraeus from a backwater into the Mediterranean’s second-busiest maritime trade hub.

This connection “would align very well with China’s strategy for the belt and road”, Broderick said.

“An early focus on investing in critical assets has given way to a new focus on connecting these assets in [belt and road] participating countries,” she said.

China had been working with members to sign trade facilitation, port, and customs agreements to reduce trade costs for Chinese exporters and importers, she said.

It leaves China well placed to play the role of “angel investor” in Lebanon, which defaulted on its international loans before Beirut was devastated by a massive explosion at its port on August 4.

“China has one unique advantage over other lenders, which is quick and ready capital,” Broderick said.

“The question for Lebanon would be the availability of other countries and companies to compete with China: concerns over Chinese influence and debt will be void if the US or other regional players do not step in and offer to help,” she said.

In turn, Lebanon’s financial crisis has upended the war-stressed economy of Syria, most of which is now controlled by al-Assad and his allies.

Damascus has encouraged Beijing to take a leading role in the UN-estimated US$250 billion post-war reconstruction boom, highlighting the scope for an overland belt-and-road trade route from Tripoli to China via Iraq and Iran.

Washington wants to prevent Beijing from making this intercontinental belt-and-road breakthrough, which would greatly increase China’s soft power. It would also tighten China’s grip on the shore-based logistics of maritime trade in the region, located at the junction of Asia and Europe. China is the European Union’s top source of imports and its second-biggest export market.

However, to make any further inroads against the belt and road, the US would first have to persuade Israel and the UAE to deny Chinese exports access to the shipping services that will soon be established between the two new diplomatic partners – a situation that seems highly implausible.

In any case, Israel’s trade with the UAE will be centred at Haifa’s Chinese-operated container terminal.

Despite US pressure, the UAE remains a leading proponent of growing ties with China. The UAE is a founding partner in the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the Abu Dhabi Global Market and the Shanghai Stock Exchange are working to set up an exchange dedicated to raising funds for belt-and-road projects. Dubai would have hosted this year’s Belt and Road Summit in April, had it not been cancelled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

“Beijing may hope to leverage its goodwill in the UAE to boost the relationship with Israel at a time when the US is pushing back on Chinese investment in the country,” Eurasia Group analyst Broderick said.

Emirati enthusiasm is driven, in part, by its need to avoid competing with the belt and road, which mirrors Dubai’s model of creating state-of-the-art sea-air logistics hubs and industrial zones like the one at Jebel Ali. Before the unveiling of the belt-and-road plan, DP World had already established its own global network of ports, including four in China – one of them in Hong Kong.

China has already established an alternative hub for its export trades at Gwadar, the focal point of the US$60 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

The largest country-specific programme of the belt-and-road plan, CPEC has vastly improved connectivity along China’s sole overland access route to the Indian Ocean first established in 1978.

Built and operated by the state-owned China International Port Holding Company, Gwadar port has recently started to handle commercial cargoes for neighbouring Afghanistan.

China is also invested heavily in Oman’s industrial free zone at the Arabian Sea port of Duqm. Valued at US$10.7 billion upon completion, it is the single largest belt-and-road project in the Middle East and represents a means of bypassing the Strait of Hormuz – and DP World’s mother hub at Jebel Ali – especially in the event of a conflict in the Gulf.

The port at Gwadar is the focal point of the US$60 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Photo: Xinhua

As a much smaller state and major trading partner of China, the UAE in 2015 took the prudent decision of promoting DP World’s ports and free zones as a pre-existing facilitator of China’s commercial belt-and-road objectives when it was launched.

Both sides have benefited from this commercial collaboration, with their bilateral trade rising by about 10 per cent a year since 2015 to reach US$50 billion last year.

However, because of the UAE’s long-standing enmity with Iran, it is determined to secure its commercial shipping through the Bab El-Mandeb Strait.

As a major participant in the Saudi-led coalition which has fought the Houthis in Yemen since 2015, the UAE has gained “privileged access” to Aden port.

At its behest, southern Yemeni separatists have also seized the Socotra Archipelago, strategically located at the mouth of the Bab El-Mandeb Strait.

This assertion of the UAE’s strategic interests has brought DP World into conflict with its Chinese counterparts over operating concessions for ports in the Horn of Africa. Despite being a coalition partner of the UAE in Yemen, in 2018 the Djibouti government ejected DP World, the long-standing concession holder for Doraleh Container Terminal, and sold its strategic stake and operating rights to Hong Kong-based China Merchants Port Holdings (CMPH). DP World sued CMPH and feuded with the Chinese and Djibouti governments – a recent memory that still rankled in Beijing, said Ramani.

Djibouti hosts China’s sole overseas military base, along with naval facilities used by the US, France and five other nations.

Chinese port operators and DP World are also at odds in fragmented neighbouring Somalia. Like in Djibouti, a 2017 agreement between the administration of the breakaway Puntland region and P&O Ports, a DP World subsidiary, to develop the port of Bosaso has fallen into dispute.

Again, China was the beneficiary – despite being an ally of the central Somalia government in Mogadishu.

Soon after being elected president of Puntland last year, Said Abdullahi Deni travelled to Beijing, where he awarded a contract to develop the Red Sea port of Eyl to state-owned China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation.

“Djibouti-style disputes and rivalries are likely in the near future,” Ramani said.

Alan Abbey, a veteran commentator based in Jerusalem, said Israel – like its new diplomatic partner the UAE – wanted to placate the US, their key security and diplomatic partner, but not at the cost of antagonising China and damaging their economies.

“Israel and the UAE share the delicate and difficult tasks of managing relations with both the US and China, whose conflicts are out in the open and growing daily. This is a long-term challenge both countries face,” said Abbey, who is a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem.

“Despite their strengths – oil and capital in the UAE and military smarts in Israel – each are small fish needing to swim with, yet dodge the sharp teeth of, two giant sharks,” he said.

Like the US, Israel is closely monitoring China’s moves in Lebanon because it has been encouraged to prop up the economy and redevelop Beirut by the Iran-backed Hezbollah political party and militia, with which Israel fought a 34-day war in 2006. Hezbollah forces have been a key component of the foreign military coalition, spearheaded by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, that turned the war in Syria in favour of the Assad regime with the aid of Russian air power.

Israel frequently launches missile attacks on Hezbollah and Revolutionary Guard bases in Syria located near Damascus.

Likewise, the US and Israel are deeply concerned by a mammoth 25-year strategic partnership under negotiation between China and Iran. Pompeo has said it would put Chinese Communist Party money in the hands of Iran and its allies in the Middle East – in particular Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthi rebels.

“Israel is no stranger to the axiom ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’,” Abbey said. “I suspect that Israeli leaders are smart enough to understand the iron fist inside the Chinese-made velvet glove of investment, cultural exchanges and joint ventures,” he said. “Yet even a love tap from such a hard hand can be dangerous to one’s health.”

China, too, has been characteristically cautious about trumpeting its potential investments in Lebanon and Syria. “We’ve seen that it’s usually others who talk up the China option,” said Guy Burton, author of China and Middle East Conflicts.

Assad had called China a “friend” and encouraged it to become a more active reconstruction partner, he said, “yet the Chinese have not said anything specific on the matter, just warm words”.

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah did the same in Lebanon and the recent talk about the China-Iran deal last month were “other examples of supposed pariahs pointing out that they have options that don’t rely on the West”, Burton said.

“But where are the Chinese in all this?” he asked. “You don’t hear them saying anything, which only adds to their allure while also increasing their stature.” ■

SCMP Research, Healthcare, Special Offer

30% discount off the China Healthcare Report 2020

Did you know that China supplies 40% of the world’s active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) for drug manufacturing? Get a comprehensive industry review and insights on Covid-19 induced market shifts from the China Healthcare Report. Purchase now and get a 30% discount before 30 Sep 2020 (original price US$400). You will also receive access to 6 closed-door webinars led by China healthcare’s most influential C-suite executives.

END

COMMENTS